Statement

Statement summary

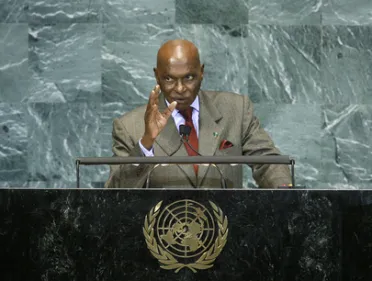

ABDOULAYE WADE, President of Senegal, citing economic crisis, environmental degradation, transborder organized crime, terrorism and drug trafficking, said the world had not changed much since the last time the Assembly had gathered. He expressed hope that solutions be found and it was natural to turn to the United Nations for such assistance. The Assembly’s focus on governance perhaps had come a bit too late. The question centred on how to make the Organization’s actions more effective in such troubling circumstances.

Continuing, he said that various “certainties” had vanished, new forces had arisen from globalization and competition, and a new world order was being defined. Emerging Powers would always be prepared to play a new role. After 65 years, the United Nations was marked by a closed historic period. The Charter bore the “stigma of colonial prejudice” and still referred to the notion of an “enemy State”. Article 38 of the statute of the Court of Justice was an anachronism and pointed to the need for reform. There were 51 Members in 1955; now there were 192.

The Security Council’s composition had changed only once, in 1965, to include 10 non-permanent seats, he said. Seventeen years of discussion on that matter had passed without much progress. Maintaining the status quo would expose that body to more criticism. “Inertia can be very dangerous,” he said. How could a credible United Nations be envisioned without a role for Africa on the Council? Senegal had argued for a permanent seat for Africa with veto rights on the Council.

Reform was also needed for the International Criminal Court. Renewing Senegal’s attachment to the Court, he said it would never be a credible body if Sudan’s President was the only one to be pursued with suspicious haste. Amid multiple crises, the question of global governance was the “order of the day”. Efforts by the G-8 and G-20 were praiseworthy, but several countries wished to see a group of high-level experts to be placed upstream of those groupings. He would dedicate himself to that task. He also had proposed an “oil against poverty” fund.

Regarding the Millennium Development Goals, he said Senegal had measured work to be done before 2015, adding that a purely quantitative approach was insufficient; more imagination was needed. Senegal had implemented a Grand Agricultural Project for Food and Plenty, which had allowed it to move from being a net importer to exporter of food. “Modern Daaras” schools taught the teachings of the Koran, as well as Arabic and French language. It was possible to provide spiritual training in schools while promoting children’s social skills. Another strategy outlined allocating 40 per cent of the budget to education, while yet another initiative addressed the school dropout rate.

Further, he said policies to promote rural women allowed them to undertake activities that had previously been in the hands of corporations. A digital solidarity initiative sought to bridge the digital divide, while an eco-villages strategy sought to give those villages more autonomy by using solar technologies, among others. In other matters, he said “Islamaphobia” exposed the moral and intellectual bankruptcy of its authors and he outright rejected it. Islam and Muslims were no one’s enemy. Islam preached respect for diversity and peaceful coexistence. He supported Israeli-Palestinian dialogue and reiterated support for Palestinians to achieve an independent, viable State. He also was happy to see progress made by Niger and Guinea-Bissau.

Full statement

Read the full statement, in PDF format.

Photo

Previous sessions

Access the statements from previous sessions.